The myth of Schubert and the guitar

Stephen Kenyon

I suspect that all instruments have their myths. These unlikely stories are perpetrated endlessly from ill-informed musical dictionary entry to record sleeve, from mistranslated anecdote to hasty programme note and on into the collective understanding of a subject on the part of musicians and the musical public at large. It should perhaps be a source of comfort that the guitar is not alone in this regard, however I would submit that it is neither necessary nor desirable for such myths to be perpetuated when a better, fairer and more honest understanding is possible.

This article examines one such myth the myth that says that Franz Schubert was one of us: a guitar player.

Nothing would please me more than to find that he was, believe me. Unfortunately the question is vexed by doubtful and contradictory evidence and a simple conclusion remains tantalisingly out of reach. However an examination of the evidence provides an intriguing glimpse into the life of this composer and into some of the aspects of the life of the guitar at this important period in its history.

Franz Schubertcomposer

Firstly, some words on the Viennese composer Franz Schubert (1797-1828) himself. Of all the composers of the past regularly attracting the epithet "great", Schubert is one of those for whom doubts are sometimes expressed as to its validity. This is largely, perhaps entirely a matter of historical accident and misfortune. When he died in 1828 very little of Schubert's work had been published or performed, and many of his manuscripts were scattered so widely that it took many decades before any kind of true overview of his achievement became possible. When that overview is made, however, it becomes plain that Schubert was a visionary musical genius of great originality who produced works of true greatness in every field save those of concerto and opera, by an age at which many other great composers are still finding their feet.

For many decades this output has suffered unnecessarily from comparison with the works of Beethoven (1770-1827). This is not the place for a detailed discussion of this matter, however the reader should be aware of the general point that we are dealing here with a composer of the absolute first rank, even though the popular view of his reputation does not consistently give this impression.

The awareness amongst some more musically aware observers of Schubert's worth must have led them to an unusual enthusiasm at the prospect that this composer may have been a guitarist. The myth of Schubert's being a guitarist at its most persistent, most colourful and ultimately, silliest, is that he was inclined to play the instrument in bed in the morning to help him write his songs. How did this idea arise?

Schubert: the basis of scholarship

Among Schubert scholars there is one name before which all others pale in comparison, and to whom all refer when in need of facts on the life of Schubert Otto E Deutsch. He did not write a biography as such, but his two definitive volumes1 "Schubert: Memoirs by his friends" and "Schubert: a Documentary Biography" collected together all the relevant and reliable data, respectively, the memoirs by friends, relatives and acquaintances, and the documentary materials relating to Schubert that has survived. These two books are neither interpretative nor descriptive, though they are copiously annotated.

The myth begins

It is to the memoirs that most attention must be made. Out of the 467 pages of miscellaneous memoir and editorial annotation, only one entry makes any reference to a guitar actually being associated with Schubert, and it seems to me it must be this entry that somehow became the seed for this element in the myth. This is an anecdote dated 1861 by one Victor Ritter Umlauff von Frankwell, relating to his father, JK Umlauff (p 375).

The most approved and able musicians of that time were (JK) Umlauff's friends and fellow artists. With the famous composer, Franz Schubert, he became acquainted as early as 1818 and they soon became good friends. He used to visit him (Schubert) in the morning, before going to his office, and generally found him lying in bed, putting musical thoughts on paper or composing at his writing table. On these occasions he often sang freshly composed songs to the composer, to guitar accompaniment, and also ventured to dispute the musical expression of certain words

My objection to the interpretation of this story as being evidence that Schubert could play guitar is two-fold;

i. Quite apart from the point that this is an anecdote at least forty years after the event, and from one who was not there, the writer does not specify who played the guitar. Taken at face value the sentence would more probably suggest that it was the singer's own guitar accompaniment rather than anyone else's as the sense of the person active ("he sang") flows straight on to "guitar accompaniments". Umlauff knew Giuliani as well as Schubert, and so might have been an active member of the Viennese guitar culture.

ii. Another person was quite possibly present at those meetings, one who definitely did play guitar. From 1818 to 1820 Schubert shared lodgings with the poet Mayrhofer, "(who) learned to play guitar so that he could accompany his own singing which, by the way, was not exactly beautiful". 2

So as far as this element of the story is concerned, we can clearly see that a sensible reading of the only guitar-related passage in the whole of Deutsch is ambiguous and imprecise at best, that it cannot on its own be read as pointing with anything resembling absolute certainty to Schubert being a guitarist, and the possible presence of a known player in the form of Mayrhofer must push this possibility further into the distance.

It is worth clarifying a further element of this story, namely that Schubert was using the guitar to help him compose his songs 3 in the absence of a piano. It is true that Schubert was almost permanently short of cash, and a guitar is of course much cheaper than a piano, an instrument he did not possess for himself until late in his life. There is however nothing in any of these records that gives credence to the interpretation abroad that it was this lack of cash that made Schubert into a guitar player, (let alone that he taught the guitar).

Returning to the question of how we understand the composer, it might not have occurred to those responsible for this gloss on the myth, but Schubert simply had no need of any instrument as composer's aid, and was perfectly capable of writing from his inner ear straight onto the music paper, as several references, not least in the above quotation, make plain.

The matter of the song accompaniments

It is also necessary at this juncture to address the wider question of Schubert's songs as they have appeared with guitar accompaniments. The Schubert-guitar myth has been widely propagated by connecting the notion of the composer using the guitar to write his songs with the idea that the final form of the songs' accompaniments is evidence of this. The fact is that, yes, several songs were published during his life, with guitar accompaniments, as was the case for many composers.

Firstly, I hope that by unpacking the story of Schubert writing songs (in bed or otherwise) while using a guitar, we start from a fairer position when looking at the question of the songs themselves. Remember, there is no definite evidence linking Schubert with the activity of using a guitar to help writing songs or anything else.

The most important question here must then be: 'if guitar versions were made, were they made by the composer?' The simple answer is, there is no way of knowing. The only direct evidence of Schubert composing for guitar is discussed below (see Terzetto for three male voices and guitar.) For the solo songs we have no handwritten versions of songs also known with piano, no correspondence with a publisher, or anything to prove his involvement with what, quite simply, was the publishers' way of making more money by selling songs to more people (like Mayrhofer, most guitar players at this time were learning guitar to accompany singing). Diabelli, whose connection with the guitar is a matter of record, published many of Schubert's songs, but any of the publishers involved would have found it easy to find somebody willing and able to knock out a simplified version of the piano score for guitar. The Tecla edition 4 of these songs printed newly arranged versions because the original arrangements were considered to be diluted to a dysfunctional degree ("they reveal sometimes serious distortions of the sources that Schubert left" p. iv). On the face of it this suggests that the composer was not involved, because surely (as we would like to think in our enlightened times) the composer would insist on more integrity for his productions.

The fact that some Schubert songs seem to have a guitar-like accompaniment is no evidence. You can find songs with 'guitar-like' accompaniments by many composers, and many of them have been published in modern transcriptions. Schubert wrote more than 600 songs, so it is hardly surprising if some of them were of that character. There are a great many more songs that have such a totally pianistic character that adaptation for guitar is totally out of the question even for a hired hack in 1820s Vienna.

Finally on this matter, Deutsch mentions the guitar versions twice in Schubert: a documentary biography:

Most of the editions with guitar accompaniment, which are not authentic, did not appear until a little later. (p. 177)

(Ref the vocal quartets Op. 11)The accompaniments to these quartet are ad libitum. The fashionable guitar accompaniments, which even appear in the complete edition of Schubert's works, are certainly not his own. (p. 225) (My emphasises.)

Even allowing there is a possible measure of old fashioned anti-guitar prejudice on Deutsch's part, these observations just about sum up the situation for the songs.

Misleading painting

The second piece of thoroughly misleading evidence was the short-lived appearance, in the Oxford Companion to Music of 1938, of a painting "Schubert as guitarist", (p. 405, plate 70 no 2) showing Schubert playing a guitar. Not surprisingly many people took this at face value, not least the voice and guitar duo who referred me to this picture as evidence of the authenticity of their performances of Schubert. However, it is clear from the style and composition of this picture that it is of a far later date than Schubert's time, and bears all the hallmarks of a romanticised contribution to the myth. The picture was dropped from subsequent editions of the Oxford Companion and Deutsch, in his listing and discussion of all the extant Schubert pictures does not list this specimen under either the authentic or doubtful headings. The picture "Schubert as guitarist" is owned by the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna whose Archivdirektor Dr Otto Biba told me that it is a spurious fabrication in a letter including the following statements:

There is no authentic contemporary picture which shows Schubert with a guitar. We have no evidence that Schubert could play the guitar. Please forget all the legends regarding Schubert and the guitar.

The foregoing discussion is intended to put in their rightful place two elements of this myth which have served to propagate it to the detriment of more valid and viable arguments. And despite the rather blunt edicts from Dr Biba it is now time to look at those aspects of the surviving evidence which support the myth more meaningfully.

Terzetto for three male voices and guitar

The first and by far the most important item is the existence of the Terzetto D. 80 for 3 men's voices, with guitar accompaniment. This piece was written in 1813 for his father's Names Day and only published much later, in common with many other works. And there really is no mistaking that it is a guitar part, as the manuscript reproduced in the 1960 Doblinger edition shows.

Largely because it has been reduced to fit into the edition the handwriting is very hard to read from the facsimile, but with the help of the engraved notation edited by Karl Scheit it is possible to see what is there. The overall impression of the writing is that it is mostly very low down in the range, with large sections occupying the four lower strings, but that it is basically playable and for the most part within what you might expect to be written by a competent guitarist.

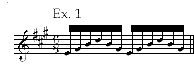

There are two distinct exceptions to this; bar 5, (Ex. 1)

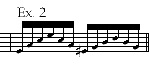

and 6 bars after rehearsal number 5 (Ex. 2) of the

Allegretto, break the cardinal rule of accompanimental arpeggio figurations in that they require two consecutive notes to be on the same string (without undertaking fingerings beyond the usual technical remit of the piece). These moments are playable, (and make perfect musical sense) but are not as idiomatic as the rest. Scheit has intervened in the first case and dropped the bass note an octave, (which makes perfect sense) but has left the second case alone.

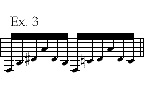

One might also query the chord change 8 bars after rehearsal number 1 (Ex. 3), which is possible but rather strange to the fingers.

Now, as we know from several decades of people asking non-guitarists to compose for us, it takes a long time before most composers get the hang of being able to write idiomatic music that falls under the fingers: many never manage to produce music straight off that is playable let alone guitaristic, as this Terzetto is for most of its length.

But I am not going to say that this is conclusive evidence for Schubert the guitarist. For one thing, it is perfectly possible that he had access to a guitarist's advice in making this manuscript: while the writing is quite hasty and uses some abbreviations it looks more like a fair copy rather than a first sketch. Moreover, the acknowledged fact that many composers have endless trouble with guitar writing is complicated by the questions of the complexity of musical function, and of the composer's aural skills.

When we speak of composers struggling to write for guitar, this is usually with self-contained concert-level writing, requiring a unified discourse expressed via a coherent texture which, in conventional harmonic language pre-supposes the existence of melodic, bass and accompanimental functions. The writing in this case is an accompaniment, supporting with a bass and simple harmonies the melodic activity of the voices. The brief solo (Ex. 4) 11 bars after rehearsal number 1 is actually texturally simpler than the outright accompanying writing, in its reliance on block chords.

So this task is less of a challenge to the composer's powers than we might think. A composer of genius and great aural acuity 5 used to hearing an instrument played in his social milieu 6, should be able to develop both an instinctual and a conscious understanding of 'what works' up to a moderate level of complexity, without having to have direct experience of playing it. Schubert was at this time only 16 years old and a precocious musician, although without the extreme stories associated with the young Mozart. Even so the musical brain-power being brought to bear here could be I think rated with the practical genius of Benjamin Britten, and probably way ahead of the composers like Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Ponce with whose guitar-writing struggles we are so familiar.

The Stauffer guitar in the Wiener Schubertbund

The next item linking Schubert to the guitar comes in the shape of an instrument in the Wiener Schubertbund. It is a Stauffer guitar 7, a Luigi Legnani model and so a fairly expensive one, in which is found the following text on a piece of paper glued to the inside:

Anton Schmid. This guitar was given to me in 1858 by my music teacher Ferdinand Schubert, being inherited from his brother Franz, Vienna, June, 1870.

Taking this at face value we have evidence that Franz Schubert owned a guitar and bequeathed it to his middle brother Ferdinand, also a musician. Let us think a bit further though. My brother would inherit a violin from me, because there happens to be one in my cupboard. I hope nobody in 135 years time will think I am a violinist though: possession in this case is certainly not proof of employment. Think also that Schmid was writing in 1870, 43 years after Schubert's death, and 12 years after receiving the instrument. What scope is there for mis-remembering names over that time-span; Franz the composer's father was also called Franz, and there were two further brothers, Ignaz and Karl. Moreover, the list of possessions at Schubert's death mentions only "clothes, shoes and hats, bedding, old music" 8, so if Schmid was remembering aright the guitar must have been out of Schubert's house when he died. While I would not take the existence of this note as a simple form of evidence in the Schubert-guitar myth, it can be put cautiously on the list of elements supportive of the story.

The remaining supportive aspects are both musical and of a more indirect nature than the Terzetto D. 80.

Schubert/Matiegka

In February 1814, a few months after writing the Terzetto, Schubert went to the trouble to take a trio by Matiegka, 9 and add a 'cello part to it. Who the intended guitarist was one cannot say 10, but it is interesting in the light of the other indicative elements. A detailed textural comparison of the guitar parts in the original trio and in the arranged quartet would be of interest to clarify further Schubert's understanding of the instrument. Like many of the composer's projects, this one was not finished.

The Arpeggione

In 1823, the Viennese guitar maker J G Staufer 7 a restless innovator in guitar design, built a bowed, fretted instrument tuned like the guitar, and called the Arpeggione. The only notable performer on this instrument was one Vincent Schuster (who was also a guitarist), and in 1824 Schubert was asked to write a sonata for it with piano, now known as the 'Arpeggione Sonata' in A minor, D. 821 and heard these days either on cello or viola, the fashion for the arpeggione as an instrument dying out very quickly 11. There are two points of interest here: firstly the coincidence that the guitar that Anton Schmid records as being owned by Schubert was also made by Staufer, and secondly that the tuning of the arpeggione was the same as the guitar, and so might be deemed suitable for a composer with an understanding of this tuning: certainly, various passages show that its composer understood how to make the good use of the fingerboard.

Towards a conclusion

I hope that we have established that there are areas of evidence that do point towards the possibility that Schubert had some experience playing guitar. I hope equally we have been able to identify the limits of certainty that are appropriate in considering these, and also to discard the spurious features of the story or myth which seem to have ballooned wildly from the Umlauff memoir and spun off into various bizarre directions.

The one thing that remains difficult to deal with is the supposition "there's no smoke without fire"in other words that he must have been a guitarist otherwise all of these myths would not have started in the first place. While it might be clear that the Umlauff story has been (mis)read with inappropriate assumptions, and the spurious "Schubert as guitarist" picture understood as such, there remain the circumstantial evidences of the Terzetto, the Matiegka project and the Arpeggione sonata.

There is however one more element of evidence to consider. The two Deutsch volumes between them contain hundreds of pages of text about Schubert, and speaking personally, having read them all, there is one thing that shouts very loudly indeed. There are what seem like endless pages of people reminiscing and detailing, and reporting about Schubert and his life: mostly his adult life, rather than the early years. And nobody, anywhere, says directly anything about Schubert playing, or being interested in the guitar. It is this deafening silence, more than anything else, that makes me question whether he did so, and makes me think that perhaps all the supportive evidence is merely circumstantial, and certainly not enough to achieve any kind of conviction. Further than that one has to wonder, if he had possessed any skill in the instrument, why, beyond the Terzetto D. 80 when he was a youth, did he never write for it as a professional adult? There was a large ready market of guitarists in Vienna, and as an extremely prolific and hard up composer from whom music poured as from a tap, would he not surely at some time have wanted to sell them some?

Summary and conclusions

I appreciate that this has been a long and involved discussion, but I hope it is accepted that this amount of detail and argument was necessary to do this complex question a degree of justice. I would like to summarise the main points as follows:

o the element of the myth that sees Schubert writing songs to a guitar in bed, because he couldn't afford a piano, and any other canards you care to name on the same theme, should be dispensed with unequivocally.

o the guitar arrangements of song accompaniments should not be seen as Schubert's own work, or versions he approved of.

o "Schubert as guitarist" the painting is spurious, however it came to be created.

o Terzetto D. 80 was written for guitar (and voices) by Schubert. How he came by that degree of instrumental knowledge cannot be said for certain: the simplest way would be by playing guitar a bit, but a composer of genius (albeit youthful) may have the aural skills to do so without.

o the Schubert/Matiegka quartet: why go to the bother of writing out a piece less interesting than you can write yourself: just because it has a guitar part?

o the Stauffer guitar owned by Anton Schmid: if properly remembered by Schmid, it may have been Schubert's purely incidentally, but it is rather a good guitar to have by accident. If it was bequeathed to his brother Ferdinand, perhaps it was he, elder by three years and a music teacher, who was the guitarist of the house, the beneficiary, perhaps stimulus, of the Terzetto and the Matiegka arrangement, and a main source of early 'education by osmosis' in guitar writing: and, as younger brothers are wont to do, an object of occasional, perhaps not very successful imitation.

o the Arpeggione: did Schuster, perhaps prompted by Staufer, approach Schubert because he had a knowledge of the guitar, or because he needed the work (and was a cheap commission), or because they really admired him, or both, or something else?

o the documentary evidence relating to Schubert predominantly concerns his adult life, and so may have missed any early teenage efforts at guitar playingthe Terzetto remember, dates from 1813, when he was sixteen, the Matiegka project a year later.

I hope the reader can see why at the outset I said that "a simple conclusion remains tantalisingly out of reach". Since it is now time to get off the fence, I would like to propose the following form of words, (or something like it,) for anyone wishing to be fair to this subject in their pronouncements:

Schubert may possibly have played the guitar in his early youth: if this interest persisted into his mature years there is little tangible evidence for it.

Finally

I will confess readily to a considerable degree of annoyance at the way this myth has spun out of control for so long, and at the way it has been either perpetuated with seemingly reckless disregard for historical validity, or used for personal ends. I will not however apologise for seeking to put into the public domain the foregoing observations and arguments in the hope that this will go some way to redress the balance, based though it is on a research base going back to 1996 (in the run-up to the bi-centenary in 1997) which fell by the wayside, but which it seemed 11 years later was needed as much as ever.

Footnotes

1. Translated by Eric Blom and published by Dent, 1946. Deutsch's thematic catalogue supplies the "D" numbers by which Schubert's works are usually identified.

2. Deutsch: Schubert: a documentary biography p354

Though a poet by inclination, Mayrhofer worked in the censor's office; he committed suicide on 5 February 1836 by throwing himself out of the office window. Schubert set over 40 of his texts, the last in March 1824.

3. as though that was the only form he wrote in, or that he needed a piano to write a song but not anything else, like a symphony.

4. Franz Schubert: Sixteen Songs with Guitar Accompaniment ed. Thomas Heck Tecla Editions 1990

5. "In addition to lessons on the piano and violin, young Franz was taught the organ, singing and harmony, and under Holzer's care both his singing and violin playing earned him a local reputation. Holzer said of his pupil:' If I wished to instruct him in anything fresh, he already knew it. Consequently I gave him no actual tuition but merely conversed with him and watched him with silent astonishment". M Brown/E Sams The New Grove Schubert Macmillan 1990 p. 2.

6. For example the picture "Ballspiel in Atzenbrugg" (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde) shows a figure understood to be Schubert seated next to a guitarist at an outdoor gathering. The guitar was an extremely popular, highly visible part of early 19th century Vienna.

7. Different sources have different spellings for the luthier's surname, with either one or two 'f's; the instrument in my collection spells it Staufer, the Wiener Schubertbund spells it Stauffer as do probably most other sources.

8. Deutsch: Schubert: a documentary biography p 834.

9. Wenzeslaus Matiegka (1773-1830) The trio Op 21 is for flute, viola and guitar. Schubert's father played the cello and it has may be surmised that the work of this arrangement was to help provide for domestic music making: (the family string quartet certainly played the young composer's early quartets). The Schubert version was originally mistaken for an original composition and published as such: recordings and performances still sometimes perpetuate this misunderstanding.

10. Deutsch: Schubert: a documentary biography p336 gives a short description of the Schubert quartet in domestic chamber music, with the composer Franz playing viola.

11. One or two modern recordings have been made of the Arpeggione sonata, using reconstructed arpeggiones, in the spirit of authentic performance. The piece was also orchestrated as a cello concerto by Gaspar Cassado and more recently recorded as a guitar concerto with string orchestra by John Williams, Sony SK 63385, in a CD release whose programme-note writer makes much of the Schubert-guitar myth.